The Florilegium of Phantasy is proud to present this story from Julie Jaquith’s “Casebook of the Mandeville Society,” a series of weird tales that revolve around the eponymous organization, which consists of a group of late Victorian gentlemen—and in some stories, as this one, a later addition in the form of Lady Abigail Rochester (née Merrycook), the wife of Sir Percival Rochester—who are dedicated to investigating any number of occult and supernatural mysteries.

The Mandeville Society, we are informed by Ms. Jaquith, was accustomed to meet every Wednesday in the home of its founding member, the aforesaid Sir Percival Rochester, which was located at No. 49 Gerrard Street, in London. Aside from Sir Rochester, and later, of course, his wife, the members of the Society were: Sir Philip Sydney, Dr. Matthew Roberts, and Dr. William Adlington. Ms. Jaquith further informs us that she has, somewhere, a series of detailed biographical notices about all of these individuals, which she may share with us in some future issue of The Florilegium.

In any case, during each meeting of the Mandeville Society—which acts as something of a framing narrative—one or other of the members recounts some weird mystery that he or she was involved in. The following story is not, chronologically speaking, one of the “first” of the Mandeville Society mysteries, but we felt—given the yuletide season—that it was a very apposite choice for the next two issues, seeing as it has a slight Christmas connection.

We hope you’ll enjoy Julie Jaquith’s “The Mystery of the ‘Fetter Lane Fiend.’”

—T. J. Quaine

“Larvas ex hominibus factos daemones aiunt, qui meriti mali fuerint. Quarum natura esse dicitur terrere parvulos et in angulis garrire tenebrosis…”

St. Isidore

The night of Christmas Eve is, perforce, a time for ghost-tales.

That this should be so—that it should be tradition, no less—must defy conventional wisdom; nevertheless, such is unquestionably the case. Attribute it to the inarguable popularity of Dickens’ novels—but Christmas Eve, that most hallowed of nights, is the singularly cosy preserve of the supernatural.

On this year, Christmas Eve happened to fall upon a Wednesday, and that is—by a curious coincidence—the traditional meeting-night of the Mandeville Society. Thus it chanced that this Christmas Eve discovered the five members of that learned body in the upstairs study of No. 49 Gerrard Street, with a comfortable fire crackling in the fireplace, and the very visible manifestations of a ferocious Christmas blizzard impotently besieging the very windowpanes that permitted them an imperfect view of the frigid, murky world without. The four men and the lady were comfortably ensconced in their wonted seats—some smoking, some drinking, some laughing and chatting, all evincing that utter satisfaction of body and mind as may only derive from postprandial contentment, and a Christmas companionship of the most congenial and complementary kind.

Now these five—and we may as well observe that they were Sir Percy Rochester, the host; Lady Abigail Rochester, his lovely wife, and the evening’s charming hostess; Dr. William Adlington, distinguished surgeon; Sir Philip Sydney, eminent explorer and indefatigable liar; and Dr. Matthew Roberts, general practitioner—were unregenerate pagans, no matter how utterly they might deceive themselves or others. Sir Rochester was—or so he proudly proclaimed—the world’s only living adherent to the Catharist heresy, a queer form of relict Gnosticism presumed extinct long ages ago; Lady Rochester accompanied her husband in heresy, but teased him unmercifully with claims that she wished to resurrect the Carpocratian and Borborite Gnostic sects, and the orgiastic rituals for which they were justly infamous; Dr. Roberts was a Roman Catholic, and thus more than half pagan to begin with; Sir Philip Sydney was an avowed Presbyterian, who knew the Bible by heart and yet, had he ever met the Savior, would undoubtedly have denounced that radical gentleman for a miscreant; and Dr. Adlington was firmly noncommittal, adopting the proverbial “wait-and-see” philosophy, a confirmed agnostic who was, nevertheless, probably more genuinely religious than any of his professedly devout friends.

And so, the following question, posed with every mark of seriousness by Dr. Roberts:

“Tell us, Rochester—tell us a ghost story. And do not dissemble! I know that you have one for us…a man of your quality could scarcely be without one. The ghost story, nowadays, is a gentleman’s most important prerequisite—and you have never been remiss, my friend, when it comes to fashion.”

Now, this elicited a laugh all round; Rochester, sucking cheerily upon his meerschaum, merely smiled, and inclined his head but slightly in acknowledgment of his friend’s petition. He was seated at his desk, with the sleek, ebon mass of the cat Cheops—black and mysterious as his dusky Egyptian forebears—forming an indistinguishable well of darkness upon his lap, and he stared into the crackling, spitting flames of the fireplace with that characteristic abstraction that seemed always to presuppose the telling of his wonderful tales.

“You know me well, doctor,” he laughed, to the great distress of Cheops. “I suppose I may oblige you with a ghost-tale…or, rather, something very like it. But that spectral Thing whereof I must treat can only very approximately be regarded what we call, κατ’ ἀντίφρασιν, a ghost; for although belonging to that species, properly so-called, the Ancients knew it by a more expressive, a more subtly evocative name. There’ll not be any rattling of chains, I fear; nor any rendezvous with past or future selves. That is a business best left to moralists and sentimentalists—it has no place in the waking world of life.”

He swiveled in his seat, to face his audience, and, resting his jaw upon a fist, and leaning slightly forward, he addressed them in those quiet, resonant tones that made the recitation of all his stories such music to hear.

“Very well, gentlemen (and wife!), very well. I do have a story for you. And it is such a story.”

A protracted puff upon his pipe; the scant evidence of a twinkle in his eye; a changeful expression upon his face, briefly glimpsed, as of some glinting facet within a jewel, betraying but the merest hint of the inestimable worth of the thing. That was ever the way with Sir Rochester—he came alive, as if waking from the sleep of life, whenever his thoughts turned to the mysteries and the wonders of the world, whenever he descanted of the myriad possibilities of the unnatural and the unreal.

“Caution, gentlemen,” whispered Lady Rochester, with an arch smile, “I foretell the prelude to a thrilling history in my husband’s expression.”

She said this laughingly, in her distinctive Connecticut drawl, which three of the assembled company found utterly charming, if somewhat uncouth—and one of their number found to be positively the most heavenly accents in all of human speech. Despite the ferocious snowstorm raging outside, here, in the homely warmth of her husband’s study, she betrayed no cognizance of it; it might have been a warm summer’s eve, preparatory to an outing at the theater, for all she was dressed, flounced on the sofa in a black satin evening gown of costly, gorgeous Paris manufacture, her sable ringlets arranged with exquisite care, her tasteful jewelry chosen with meticulous attention to color and mood and light. With her stunning figure and a beauty that was one part American wholesomeness and two parts Continental sensuality, she made Madame Gautreau seem but a coarse and callow girl; she was a young, pretty rose-bloom, all the more distinctive by contrast to the dull, aged thornbushes amongst whom she blossomed.

“I am prepared to hear it,” she continued, a mocking light in her pale blue eyes, “but then I am very young. But I worry about you elderly gentlemen: I fear your hearts may not be equal to the strain.”

From the twain doctors, impatient dismissal of her fears; from Sir Philip Sydney—uncommonly quiet this Christmas Eve—no sign at all that he had even noticed the question. His nose was buried—as it had been all evening —in the Illustrated News, wherein he feigned a kind of obliviousness to the company and the discussions of his friends. That it was all a show, that it was all a studied display of contemptuous indifference and disinterest, was plainly evidenced by the very singular fact that—although he must have been reading the particular article that engrossed his attention for well over an hour—he had not once turned a page.

“Sydney!”

Lady Rochester had never been afraid to remonstrate with the great, bullish explorer—a man whose disdain for womankind was as notorious as his willingness to express it.

“Put up that scurrilous rag, and attend Mr. Rochester.” She never referred to her husband as “sir,” his baronetcy notwithstanding, nor signed herself as “lady”—an egalitarian quirk of her American upbringing, no doubt.

“Shocking behavior, Sydney…shocking!”

And Sir Sydney complied: he put down the paper, with no protest, and seemed not a little abashed at her harsh words.

“Well,” Dr. Roberts finally said, “we are all listening, Rochester. Tell us your story—and omit nothing! I mean to be terrified tonight, and shall be disappointed with anything less than a sleep troubled by persistent nightmares.”

Everyone laughed, including Sir Sydney, but Sir Rochester gazed out the windows, pondering the snow-flurries in a blue mood of abstraction. The three men and the lady of his audience waited patiently for him to begin his story, which they knew could not be far off. That patience was presently rewarded, for Sir Rochester shrugged off the memories that dogged him, and turned once more to his friends.

“You want a ghost-story, doctor? Well, I believe I have one for you. But I warn you at the outset—it is not a satisfactory one, it has very little of the spiritual or at least didactic comfort such tales are commonly required to possess. No, it is disturbing—utterly so—and it is baffling, as encounters with the Unknown invariably are.”

And, on that dark Christmas Eve, with the snow-flurries beating furiously upon the streets of London, and all thoughts of Yuletide warmth and cheer long fled from the city, Sir Percy Rochester proceeded to recount THE MYSTERY OF THE “FETTER LANE FIEND”—:

“My story is set many years ago,” began that experienced teller of tales, “well before I met any of you gentlemen, long before I met my beloved wife, long before there was a Mandeville Society. I did not then live on Gerrard Street, for those were impecunious years, ere my dear brother died on the dusty streets of Khartoum in the arms of the hero Gordon—in short, before I inherited the Rochester fortune, and all the freedom and its lack such condition entailed. Moreover, I was but recently returned from Scotland, and more than usually impoverished—spiritually as well as financially—in the wake of its disagreeable ordeal. So I let a modest apartment on Cheyne Walk, really a very villainous-looking place, inhabited by a villainous-looking assortment of human dregs and debris; but it suited my needs admirably, and conduced to my scholarly hermitry; and I had not then, anyhow, the vast collection of tomes and curios that I now possess. And…well, if you will pardon the expression, I was a one-man Mandeville—and, my dear friends, all the poorer for it.

“Be that as it may, I was keenly alert, as ever, for any sign of the outré and the unnatural—the only adversaries I own worthy of the queer predilections of my intellect. ‘Τὸ ὄργανον τῆς γνώσεως ἴσθι,’ was my father’s favorite adjuration—‘be an instrument of knowledge.’ I have always cultivated that as a sort of personal motto, you know; and the queerer and more uncanny that knowledge, the better I liked it, and the more dearly I coveted it. And I made sure that my friends knew this; oh, I had no want of suppliants in those days, applying to my, er…peculiar erudition. So I was pleased, though not altogether surprised, when an old acquaintance of mine appeared upon my doorstep one day —and no less a one than my old friend Inspector Bascombe, formerly of the Edinburgh Constabulary, and who was then but recently with Scotland Yard.

“To come to the crux of the matter, Bascombe had a deuce of a mystery on his hands (the man has an uncanny knack for such), and he was at his wit’s end. To his mind—an uncommonly keen one, whose judgment I have always valued—the insolubility of the case admitted not a little of the supernatural, and so, bearing my open invitation in mind, he had obtained permission from his superiors to present the facts in the case to my unique understanding. He bore an ominous-looking black valise with him, big with mystery and the allure of the unknown, wherefore I bade him disgorge its contents.

“Over the subsequent hour and a half, my old friend and I pored studiously over the curious materials he had collected about a baffling and utterly disturbing series of grisly murders, which the sheets and penny dreadfuls gleefully attributed to a miscreant they had dubbed—with a predictably puerile luridness—the ‘Fetter Lane Fiend.’ Now, gentlemen, I do not expect you to be familiar with that name (still less you, dear wife…savage child of the New World that you are)—no, I judge by your expressions that you do not recognize it. Small wonder!—for, despite the unknown perpetrator’s colorful agnomen, it was really very little-heralded in the press. This was, of course, long before all that awful ‘Whitechapel’ business, when the most terrible ‘Jack’ we knew was that spring-footed prankster of an earlier generation.

“But the murders of the ‘Fiend’ were quite as appalling, and I well remember how great was the dread of young men and women to venture out of nights upon Fetter Lane, and the adjacent districts of Fleet Street, Holborn, and Chancey Lane. The murders were five in number, and so ghastly were they, that the authorities attributed them only with great difficulty to human agency at all. They appeared more the work of some feral beast, some infernal brute of the kind long banished from the haunts of civilization; such was the savagery of the attacks and mutilations, such the utter ferocity and elemental hatred—for that is the only word for it—manifest in the manner and method of the slayings, that men could scarcely credit the workings of a homely human intelligence.

“The killer seemed indiscriminate in his choice of victims, for there was no pattern readily discoverable—they ranged from lowly prostitutes and beggars to the uppermost rungs of gentility (often very little difference between the two classes these days, admittedly); there was no preference either for sex or age; and the motive of mercenary theft could not be entertained, for in several instances items of no little worth were left unmolested upon the corpses. As to the condition of these latter…well, that constituted the most horrible detail of the whole nefarious business. They were one and all of them mutilated and debased in so cruel and inhuman a fashion, that even stout old Bascombe was hard put to retain his composure—the stolid Scotsman covered his face and begged a bracing tot of brandy at recollection of those gruesome scenes!

“To epitomize, their faces were uniformly obliterated in the most unspeakable fashion; they were eviscerated, dismembered, disemboweled, and in such manner that, according to the judgment of the coroner, the wretches yet lived for some time thereafter. Moreover, their eyes were plucked, roots and all, from their very sockets—as if the Fiend thus hoped to evade detection, supposing, as the superstitious do, that the retinae of the dead may impress upon their photosensitive tissues the last scenes beheld in life. In no instance did the killer leave behind any betraying vestige.

“But that is not to say there were no witnesses, for these there were—after a fashion. Yes, but their character was not unimpeachable, and their testimony was considered by the Yard to be—at best—scarcely worth crediting. A few were pimps and prostitutes; others were a drunkard, or an opium addict, or a friendless writer of lurid tales, for such are the worthless flotsam that frequent the London streets in the small hours of the night. And yet, whatever may be the trustworthiness of these witnesses, whatever their credentials or standing in society, there was a remarkable concordance in their disparate accounts.

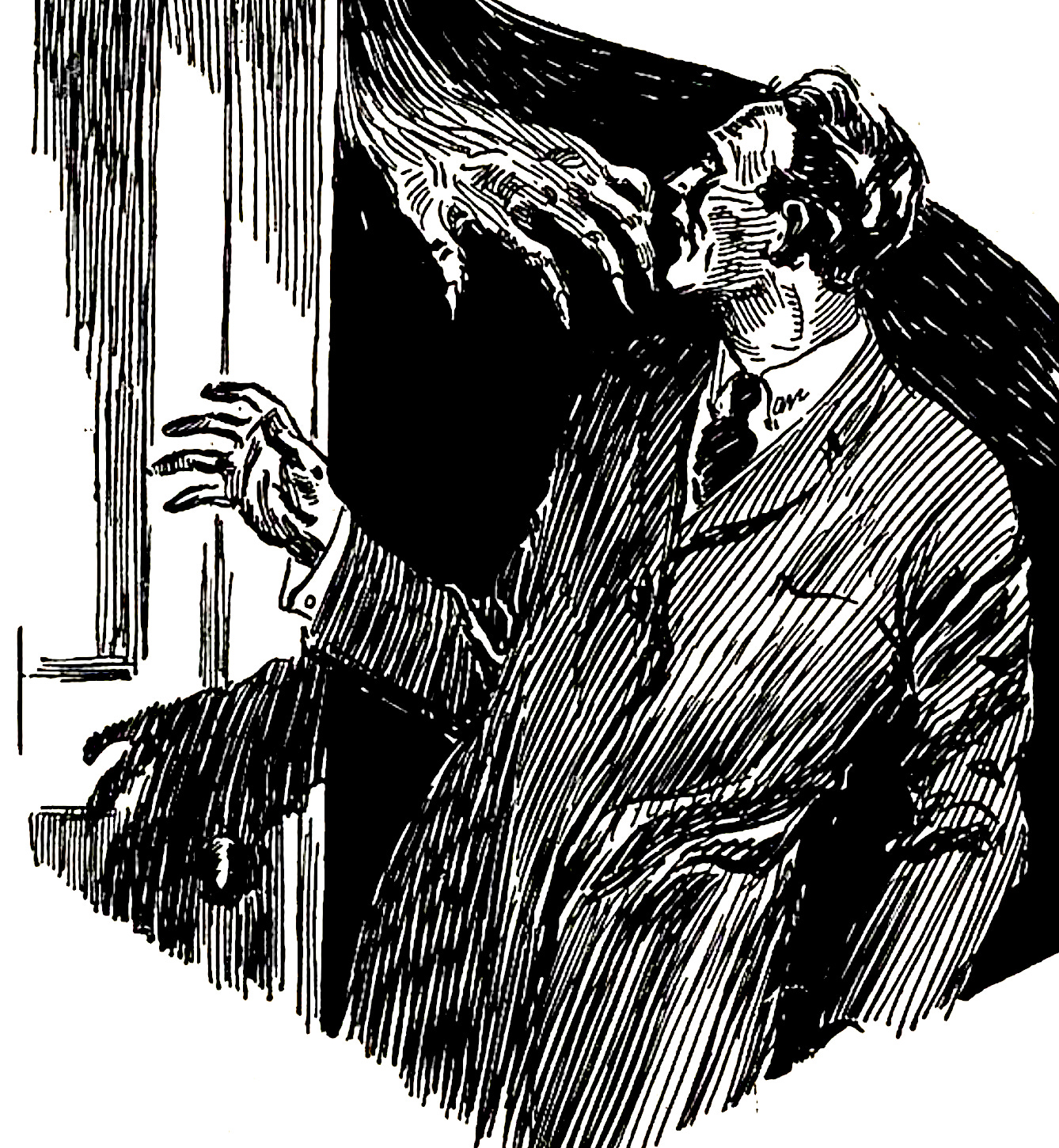

“None of them actually beheld the murders in the act of commission, you see; they were the sort of chance eyewitnesses who happened to be nearby, at about the estimated time the slayings occurred, and who recalled noticing a skulking figure, mayhap, or hearing a queer sound echoing in the night. In some instances, there was indeed a figure to be seen, slinking down an alley, or stealing from shadow to shadow between the little pools of flickering illumination cast by the gaslights. They descried—each of them, without fail—a ghastly, pale figure, ‘a shambling shape of horror,’ according to one man’s account. Most curiously of all, the size of the figure was depicted as astonishing, for it was said to be colossally large, many times the girth and height of an ordinary human being. A giant, they said, a pallid, bloodless ghoul was the culprit; they could recall no distinguishing features, and were curiously reticent to even suppose it a man—they accorded in labeling the thing a ‘vampire,’ or a ‘rawhead and bloodybones’ or some such bogey of childhood nightmare. One of the more aged of the witnesses was convinced that it was ‘ol’ Springheel hisself;’ but I have encountered Jack in my time —or, rather, that devilish apparition that men, in their merciful ignorance, have thus euphemistically denominated—and you may be certain the Fiend was not he.

“Only one other clue, and that a singularly unhelpful one. One witness—connected with the last murder, that of a rather well-off shipping officer named Maxim Fairborough, I think—claimed to have actually heard the voice of the ‘Fiend,’ and, what is more, to have seen it. This man—who, for the sake of disclosure, was the aforesaid opium addict—testified to hearing the awful sounds of a violent struggle, and a human screaming, emanating from the shadows just without the gaslit circle wherein he tottered uncertainly after the night’s debauch. Startled, drug-befogged, and unsure what to do (he was not a courageous man, and gladly owned it), he merely remained put, straining to listen to what he could only suppose were the sounds of a man’s horrific death—if it were not, indeed, merely an hallucination generated by his noxious habit. But presently, even these sounds ceased, and the man strained his hearing to the utmost—feeling himself beset by the most awful feeling of acutest danger. Given the preternatural sharpness of sense that is the common side-effect of the opium habit, I believe that the man’s capacity in this direction was rather greater than it might otherwise have been, and certainly much greater than the inspectors gave him credit for; however the case, the man’s affidavit claims that he heard a low, decidedly evil-sounding gibbering and chattering noise, something like the gnashing and snapping of teeth, not far beyond his gaslit ambit. The mere remembrance of it seemed to provoke a fit of ague in the man (or was it merely delirium tremens?), and he distinctly recalled a presentiment of being ‘watched’ by something—whether man or animal he could not say—that lingered menacingly in the shadows.

“Suddenly, he descried what he took to be a face looming out of the darkness; a bloodless, sickly expanse of cadaverous white flesh hove into view, ill-lit by the sputtering gaslight. It was, said the opium addict (and none believed him, though the bobbies took down his testimony just the same), a great, hairless human head, much vaster than any he had ever seen (he claimed to be a sometime dabbler in phrenology, and thus uniquely versed in the recondite arcana of human cranial physiognomy), with a grotesque, featureless, shadow-strewn face pendent beneath an enormous, pallid brow. There were eyes—yes, two tiny, yellow eyes, without mercy or compassion or soul, and emitting such an expression of evil that the man would have fainted straightaway, had he not been so bloody inoculated with his chosen poison as to be utterly insensible to normal, autonomic responses. But there was more to the awful apparition. It had a mouth, yes, and teeth—and the only color he descried on the thing was spattered about that gruesome maw: flecks of crimson, dribbling rivulets of gore, and clinging bits of viscera.

“Overcome with terror, the addict fled the place with considerably more haste than dignity, flying from gaslamp to gaslamp, and all that time—he swears—he could hear that dreadful sound of tittering and chattering at his very heels, and the dull thudding of immense and heavy footfalls, until he turned onto Fleet Street, whereafter his pursuer (if pursued he was) seemed to have quit the chase. The only further intelligence to be gleaned from this witness was some sense of the possible identity of the ‘Fiend’—the detectives asked him to determine, if he could, any meaning in the whispered gibberings of the unknown pursuer. The man claimed there was little to be understood in them, even were he not frightened half out of what little wits remained to him; however, in hindsight, he seemed able to assign a language to the curious mouthings, and was inclined to believe they represented some peculiar dialect of Greek. Accordingly, and although the Yard placed very little confidence in this man’s testimony, they included Greek as the probable ethnicity of the ‘Fiend,’ and conducted a fruitless and entirely ill-advised search of the Greek Quarter, which nearly threatened to erupt into a racial conflagration ere they were through. Chastened, the fools decided to follow up another lead—someone conceived the brilliant notion, derived from the eyewitnesses’ insistence on the Fiend’s great size, that they ought perhaps to search for a deformed acromegalic, and so they hunted up street-performers and sideshow acts, hoping to find some poor lusus naturae to fit the bill. But I suppose I shouldn’t malign them so—for they were desperate, terribly so, and as was the case with Bascombe, they could think of no good reason not to pursue every available lead, no matter how unpromising. But really—they are the most deucedly incompetent bunglers!

“Well, gentlemen, such was the most detailed accounting of the ‘Fiend’ that could be gotten—shapes ill-seen, sounds ill-heard, and very little else besides. Bascombe confessed to me that the matter was, for the nonce, utterly impenetrable to the Yard (I did not doubt him), and that they had pretty well given up—though that was not, of course, their official position. But he recalled my interest in these strange sorts of matters, and decided to have a go at it. I thanked him for this consideration, and promised that I would exert my powers to the utmost; if nothing else, I assured him, his mystery would have another and perhaps fresher set of eyes to review the facts, and mayhap detect what others had not.

“The truth was, though immensely intrigued by the abovementioned peculiarities of the case, I bid fair to disregard the whole matter. You see, I felt there was very little in the affair to justify Bascombe’s application to me—in short, I believed it constituted little more than a case of quite typical mundanity, involving some vagrant maniac skulking in the shadows of Fetter Lane, or perhaps some more dedicated ‘thrill-murderer.’ The hints at vague and unnatural shapes are not an uncommon feature of witnesses’ testimonies, especially when the quality of those involved was accounted for; and the queer noises may have represented any number of things. The only common thread inhering in the victims’ lives was their uniform patronage of a quaint little Fetter Lane antiquities junk-shop, whose proprietor had been murdered some weeks before the ‘canonical’ murders of the Fiend began. However, this connection had been thoroughly ‘followed-up,’ the peculiars of the proprietor’s murder did not wholly match those of the later slayings, and no resolution to the mystery was discovered anyhow in that quarter; after a week or two of close surveillance at the junk-shop, it was evident the Fiend was not to be thus easily encompassed. But to my mind, it was obvious the murderer was an habitual malingerer of the mercantile district; doubtless, he had begun his diabolical spree in clumsy fashion with the slain business-owner, and after a fallow, post-necine period—common with first-time killers—the Fiend had resumed his murders, advancing in skill and efficiency. Here was no mystery for me—assuredly, the culprit would soon be apprehended lurking in the byways of the Lane, harassing prostitutes or scuffling with pimps. No, gentlemen, it was the kind of sordid human business I thoroughly detest, and I thought Bascombe’s visit was merely one of desperation; the mystery of the ‘Fetter Lane Fiend’ dropped completely from my mind (which was, if I recall correctly, exercised quite vigorously at the time by the Mystery of the Martian Mummy—but that is a discussion for another session). For the whole of the subsequent week, I had not occasion to think of it again.

“That was, however, by no means the end of my association with the affair. The mystery of the ‘Fetter Lane Fiend’ was thrust back into my consciousness after the week had elapsed, and that by a means most unexpected. It happened as I lay in bed one morning, puffing merrily away upon my pipe, dispelling the last, cloying clouds of Somnus from my addled brain. That is, you know, when the great majority of my most brilliant ideas have come to me”—here Lady Rochester snorted, and muttered something snide and unrepeatable beneath her breath, which was pointedly ignored by the speaker—“it is when my imagination, yet surcharged with the dissipating atmosphere of dream, is at its wildest and least constrained.

“Anyhow, I sat thus in a profound abstraction for the better part of the morning (for in those days I had not my dear Abigail to divert me from my funks). Perhaps I might better call my spell that morning a sort of self-induced trance, of a kind that only the most signal intellects may achieve (hold your tongue, Sydney—I will not have you interrupt me with your impertinent snickers!). I sat thus, as I said, and my brain made connections subconsciously that, in all likelihood, the conscious faculties could not have drawn. In a word, I made a linkage—and a very curious one at that.

“It seems simple, really, in the unobstructed looking-glass of hindsight, but I still marvel that I made the connection at all. It consisted in the recollection of a minor news item I had read several months before in the Illustrated News, about a group of boys who had discovered a cache of old Roman artifacts somewhere on Fetter Lane. Nearly coincident with the remembrance of that matter, I conned the full import of all that talk of ‘chattering’ in the night; and I remembered the interesting things that certain of the Ancients had to say about terrifying specters in the dark places of the earth. In particular I recalled certain of the bogies of the aboriginal Italic religions, and I minded me especially of a queer line in Isidorus’ great encyclopedia, about the disagreeable predilections of the ‘larva garriens’—the ‘gibbering poltergeist’ of Roman superstition. Just these two matters—some boys and their chance discovery, and the incoherent, scarcely creditable ravings of an opium addict anent a ‘chattering’ or ‘gibbering’ Thing in the darkness. Two items, certainly, that seemed not to bear the least relationship to one another; yet—as I now realized with mounting excitement—there was indeed a connection, oh yes, and that a most intricate and terrifying one.

“I spent that morning in a veritable frenzy of research. As now, I kept archives of the newspaper, an eminently reasonable practice that has served me in good stead on many occasions; I flew into my library—which was a much poorer thing than I now possess—and hunted sedulously for the article I sought. I eventually discovered it, after a great deal of time and swearing, and it did much to affirm my suspicions. Two boys, as I had thought, claimed to have discovered some rather remarkable Roman relics, whilst digging about in a small plot of undeveloped land hard by one of the Fetter Lane establishments—that very establishment, in point of fact, that had figured in the investigation, only to be dismissed for want of evidence. The artifacts, according to the helpful etchings accompanying the article, were a small bronze figure, of the charming Hercules mingens type—crude of subject but exquisitely executed—and several rather handsome silver denarii bearing the cruel countenances of Severus and Caracalla.

“Now, the substance of the discovery was only this: I had a clue, and the name of a Fetter Lane business that—if my supposition was correct—must overlie a Roman ruin of some considerable significance. My friends, I am sure that the importance of that conclusion must elude you; for the time being, it must continue to do so. What matters is that a petty and entirely middling (to my mind) police mystery had suddenly transformed, in the course of a single morning, into a dreadfully occult and outré problem of the utmost magnitude. Wherefore, I had recourse to my tomes. I rang for lunch—for I had a manservant then, not faithful Hodgson, but a morose and skulking fellow whom I could never trust, and whom I roundly abused at every least opportunity till the wretch finally deserted me—and I expended the better part of the early afternoon in the elucidation of the absorbing problem that so fearfully oppressed my mind.

“Though my library was, as I said, a much less impressive affair in those days, I had nevertheless the great nucleus of hoary volumes that yet composes the core—and oftenest consulted—element of my collection. Soon, my study floor was littered with wide-flung books; I scoured volume after volume, seeking the benefit of ancient wisdom and queer and forbidden learning. I searched through works both obscure and well-known—the magical writings of Apuleius, the aphorisms and traditions of Simon Magus, the recondite tract Le Livre du Démiurge by Raymond de Toulouse, the Physica Curiosa of Caspar Schott, the Magical Disquisitions of Delrio, De Praestigiis Daemonum of Johann Wierus, the Book of Zoroaster, the Secret Book of John, the Seventh Cosmos of Hieralias the Prophet, and the demonologies of Lavaterus, Theodore the Archimandrite, Cardanus, and Agrippa. I furiously scribbled notes as I went, wondering if any of this antique knowledge—forgotten, traduced, scorned by modern science—would avail me at all in the final contest.

“At half past two, I sallied forth to meet with a bank solicitor, one Charles Efferning, who was currently overseeing the disposition of the ‘Antiquities, Ltd.’ curio shop upon Fetter Lane, whose proprietor—Jack Delacourt—had died intestate, and by means most gruesome, several months earlier. At a quarter past three, I dispatched a note to Insp. Bascombe, informing that gentleman to foregather with me at five o’clock that evening, at the Antiquities, Ltd. storefront on Fetter Lane. And I let hint, in my modest way, that he could expect a very significant break in the case of the ‘Fetter Lane Fiend’—‘and for goodness sake,’ I further adjured him, ‘do bring along a brace of “bobbies,” the each of them equipped with bull’s-eye lanterns, and suitably weaponed.’

“Having thus prepared for my great adventure, I repaired to my home on Cheyne Walk, stiffened myself with a tot of brandy (I was inexcusably green in those days), and looked me to my own weaponry. My preparations in that sphere were quickly accomplished—for, as you know, my implements for battling the Unknown are threefold in nature, and they are never far from my person. The first, and most potent of these, was my own unique and incomparable brain—and for the comportment of this most useful organ I had already arranged, in the quaffing of brandy. The second, and far cruder tool, consisted of my Colt .36 Navy revolver, a weapon that has never yet failed my purposes, ever since first I acquired it during my time in America. And the final of my weapons I retained lest the other two fail me—my dear mother’s thirteenth-century Latin translation of the Gospel of Philip, a bit tattered, worn, and dog-eared, but very comfortable in my jacket breast-pocket all the same. Although spiritually I own myself a Cathar—perhaps the only remaining, in this heathenish age—I nevertheless find this curious Valentinian tract a handy helpmeet in my confrontations with the unnatural; so if I felt myself a bit hypocritical with its inclusion amongst my ammunition…well, who among us can truly disclaim all hypocrisy?”

[Thus concludes the first part of “The Mystery of the ‘Fetter Lane Fiend.’” Please join us in the next issue of The Florilegium for the thrilling conclusion, in which Sir Rochester recounts how he did battle with the Fiend in the Roman catacombs beneath London.]